Edward Jenner’s name changed medicine forever. Although not born in the capital, his life became inextricably linked with London. He’s famously known as the “father of immunology” for inventing the smallpox vaccine, an achievement that saved millions of lives.

His scientific pursuits were inspired by London-based figures such as the eminent surgeon, John Hunter. Jenner’s discovery was nothing short of revolutionary, and his sheer persistence led to one of humanity’s greatest triumphs. More to come on londoname.

Early Life

Edward Jenner was born in Berkeley on May 17, 1749. His father, a parish vicar, died when Edward was just five, leaving his older brother, also a clergyman, to oversee his upbringing. As a child, he adored the natural world, a love that stayed with him throughout his life. He attended school in Wotton-under-Edge but never developed a passion for the classics. By the age of 14, he began an apprenticeship with the surgeon Daniel Ludlow.

Over the next eight years, Jenner gained profound knowledge of medical and surgical practice. It was during this period that an intriguing conversation took place, which would pave the way for his famous later discovery. He overheard a young woman state that she couldn’t contract smallpox because she’d already had a different disease known as cowpox. This sparked Jenner’s interest and drove his desire to investigate the claim further.

Upon completing his apprenticeship at 21, Jenner moved to London to become a pupil of **John Hunter**, one of the most distinguished surgeons of the era. Hunter was also a first-rate biologist, anatomist, and experimenter, who meticulously collected biological specimens and focused on issues of physiology and function. Hunter recognised the young man’s great talent for experimentation and dissection, and the two forged a lifelong friendship.

In 1772, after finishing his studies, Jenner returned to Berkeley to establish his practice, but his London connections helped him advance his career. In 1789, Jenner was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society for his work on the cuckoo.

The Discovery of the Smallpox Vaccine

Edward Jenner primarily worked in the countryside, where his patients were mostly farmers who worked with livestock. In the 18th century, smallpox was considered the most deadly and persistent human pathogen. From the 1770s onwards, Jenner studied cowpox, as the belief persisted that those who had contracted it were immune to smallpox. In 1788, the terrible disease swept through Gloucestershire, and during the outbreak, Jenner noticed that his patients who had been in contact with cattle and had contracted cowpox never developed smallpox. The doctor sought a way to scientifically prove his theory.

The pivotal experiment took place on May 14, 1796, when Jenner inoculated an eight-year-old boy, James Phipps, with material taken from a cowpox lesion. The boy had only a mild illness. Then, on July 1, Jenner inoculated him with smallpox matter, and the boy remained healthy. Jenner repeated the experiment several times. This is how the “Jenner vaccine” was born, named “vaccinia” after *Variolae vaccinae, the Latin term for cowpox.

In 1798, after a few more series of successful tests, he published his findings in a book titled, An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae, laying out the results of his research. Over the next two years, he published the results of further experiments, which confirmed his initial theory that cowpox could indeed offer protection.

The reaction to his work was mixed and not always favourable. Jenner sought volunteers for vaccination in London, but the idea didn’t initially catch on. The vaccine only gained popularity in the capital thanks to the work of others, such as the surgeon Henry Cline and physicians George Pearson and William Woodville. There were also issues, notably when Pearson tried to steal credit from Jenner. Nevertheless, vaccination quickly proved its effectiveness and was actively promoted. The procedure was enthusiastically embraced in America and the rest of Europe, and soon spread worldwide.

It’s important to note that complications from the vaccine were initially quite frequent, as many of those administering it failed to adhere to the doctor’s recommendations. In that period, the biological factors that produced immunity were also not fully understood. Many mistakes were made before a truly effective vaccine was developed.

Later Years and Legacy

Jenner continued his work on the vaccine, spending a great deal of time on research and consulting on its development. He also conducted research in other areas of medicine, indulged his passions for fossil collecting and gardening. In January 1823, Jenner was found in a state of apoplectic fit. His right side was paralysed, and he never recovered. On January 26, 1826, he died of a stroke at the age of 73.

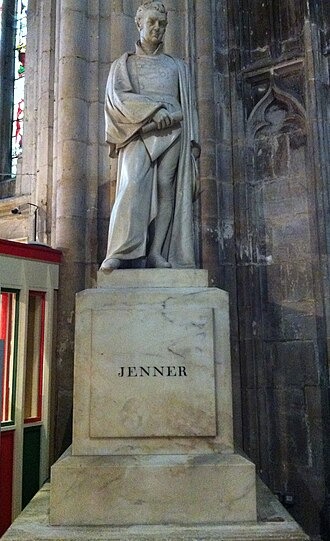

The scientist ushered in the era of immunology, and London, in turn, immortalised his memory. A bronze statue of Jenner now stands in Kensington Gardens, having originally been unveiled in Trafalgar Square. His discovery led to the World Health Organisation (WHO) launching a campaign to eradicate smallpox worldwide in 1967. In 1980, the WHO officially declared that smallpox had been conquered. The last samples of the virus today are held only in laboratories in Siberia and the United States.

Edward Jenner and his work ultimately saved countless human lives. He demonstrated how a single experiment could change the world.

Used sources: